Jane Dieulafoy is another excellent addition to our series. She’s like something out of a fiction novel. A vibrantly brave woman, born out of context with the Victorian world. Her early marriage to her partner in life, her unusual dress, and her service in the French army, all make her beyond fascinating.

Jane was born July 29, 1851 in Toulouse, France. Her father died shortly after her birth, leaving her, her four sisters, and her mother behind (Gran-Aymerich 2006:35, Adams 2010). Fortunately, she seems to have come from a well off family, and was sent to study with the Sisters of the Covent of the Assumption in Auteuil not far from Paris (Gran-Aymerich 2006:35). She excelled in her studies, learning several languages and honing skills in drawing and painting that would later serve her well (Gran-Aymerich 2006:35).

She never showed an interest in the household or womanly work, though there was one person who was able to temp her into matrimony. Marcel Dieulafoy was perhaps the only man who could have married the unorthodox Jane. Marcel was a man of action and adventure, well studied and restless a bit unorthodox himself (Gran-Aymerich 2006:36-37). Jane was 19 when they married and they agreed on a new way of life when they married, for Jane never wanted to be ruled over by any spouse (Gran-Aymerich 2006:36-37). They agreed to a marriage of equals and for the rest of their lives didn’t waver from those vows (Gran-Aymerich 2006:37).

The first test of those vows was the outbreak of war. When the war against Prussia and Germany broke out in 1870, the Prussians laid siege to the Paris walls (Adams 2010:45.) Marcel joined the Engineering corps and Jane followed after him. She dressed as a man and became a noted sharpshooter (Adams 2010:45.) She participated in every mission with Marcel and somehow managing not give away her secret (Coudart 1998, Gran-Aymerich 2006, Adams 2010).

Marcel did have a civilian job as a railroad engineer, to which he returned to after the war. Still, the world and archaeology called to them both, and the lure of adventure overseas convinced Marcel to leave his job and he and Jane went, together, to investigate Persia.

The First Persia Expedition.

The Dieulafoys first trip to Persia did not go exactly as planned; from all accounts they had rough going, poor weather, and both of them caught high fevers that persisted long after they returned home (Gran-Aymerich 2006, Adams 2010.) Despite all of this, the Dieulafoys fell in love with Persia, forging strong friendships that would serve them well later on.

The Dieulafoys traveled Persia for two years starting in 1881. To all observers they were two men out on their own, left to their own devices and responsible for their own safety (Adams 2010:48.) Photography was still new and Jane’s camera became their best ambassador, allowing them to offer photos to the local in exchange for wealth of images of their own. Jane photographed everything; people, places, and especially buildings (Adams 2010:48.) Her photos greatly expanded the field of artifact and architectural study and eliminated the unintentional errors created by the individual interpretation by artistic depictions (Gran-Aymerich 2006:44.) These images of Persia collected on this first trip are still considered one of the greatest of contributions of the 19th cen (Gran-Aymerich 2006:44, Adams 2010:48.)

Jane also kept a journal, recording everything that occurred during their trip and these notes came in handy when she returned home. While recovering from the fevers that accompanied them back from their first trip, Jane began her writing career. She published her writings about their travels and the early glimpse of Susa in her book Le Tour du Mond (Gran-Aymerich 2006:39, Adams 2010:48.) It was incredibly well received, and she quickly became a celebrity for her writing.

Jane wrote about everything, since everything interested her. She was a historian, archaeologist, sociologist, and political wonk (Gran-Aymerich 2006:43.) Victorian readers loved her accounts, and Jane became a celebrated woman writer. This would later influence her to create the Prix Femina in 1904 along with other well know female writers (Iranica 1995, Gran-Aymerich 2006:57, Adams 2010:60, Zagria 2012.) This award was meant to celebrate French female writers, as either gender could win the prize, but the jury was always completely female (Adams 2010:60.)

The Dig in Susa

The brief glimpse of Susa was not enough for the Dieulafoys. They knew the archaeological poetical in Susa was great, and through the use of the relationships they forged in their first expedition, and a little political muscle from Louis De Ronchaud, they were able to get permission and funding to excavate in Susa (Gran-Aymerich 2006:45, Adams 2010:49.)

The Dieulafoys and their small team reached Susa in 1885 in the spring. This time they brought with them Charles Babin, a civil engineer and Felix Houssaye, a naturalist, with them (Gran-Aymerich 2006:45.) The small team set up camp near the worksite and began the task of hiring local men to work. The crew ran towards an upwards of 300+ men from various tribes around the area, which caused conflict outside of the dig site, but inside the boundaries, the Dieulafoys managed to keep the peace (Gran-Aymerich 2006:47, Adams 2010:46.)

It’s reposted that Jane was the one to grab a pick-ax and strike the first blow at the site (Adams 2010:51.) From there she not only lead her own massive crews, she supervised the excavation of the trenches, recorded the artifacts found, and kept the site journal (Gran-Aymerich 2006:47.) Jane’s methods of recovery mirror very closely the methods of today: plan maps, location placement, photographs, and find numbers (Gran-Aymerich 2006:48.) All that’s missing is a GPS point.

The excavations at Susa started with a reexamination of W.K. Loftus’ work earlier. During this, Marcel noticed that a layer of what Loftus called ‘sterile clay’ was really a clay cap covering the now famous Lion Frieze, which guarded the entrance to the monumental palace of Artaxerxes II (Gran-Aymerich 2006:47.) These brightly glazed bricks were meticulously recorded by Jane, marking the exact placement of each brick, which allowed for an exact reconstruction of the Frieze later on in the Louvre (Coudart 1998:68, Gran-Aymerich 2006:50.) This Frieze was the first of its kind to be found in Persia, but not the last (Gran-Aymerich 2006:47.)

The weather was harsh during the excavations. From February through March the rain was so bad they often couldn’t leave their tents (Gran-Aymerich 2006:47.) It was this same bad weather that convinced them to close the site for the season. But they would be back sooner than they expected due to politics. The Dieulafoys carefully packed all of the glazed bricks of the Lion Frieze to ship them back to Paris. However, the customs officials of Persia refused to release the artifacts at first, despite an earlier agreement to do so (Gran-Aymerich 2006:48) The Dieulafoys, along with Babin and Houssaye returned to Persia to convince the officials to release the artifacts. Since they were already back, they all decided to return to the site at Susa and continue work.

This time the team focused on exposing the grand palace of Artaxerxes II (Gran-Aymerich 2006:49), and Jane again assumed the role of record keeper and crew leader. It was here that the team noticed the discoloration beneath the floor stones, and upon digging into the discolored floor, found the remains of Darius I’s original palace, which had been destroyed by fire in the time of Xexes I and buried under gravel only to be restored by Artaxerxes II (Gran-Aymerich 2006:50). As they recovered both palaces, they again found a beautiful Frieze of a parade of expertly pained men, which became known as the ‘Frieze of the Immortals’ the second such frieze discovered in Persia (Gran-Aymerich 2006:50.)

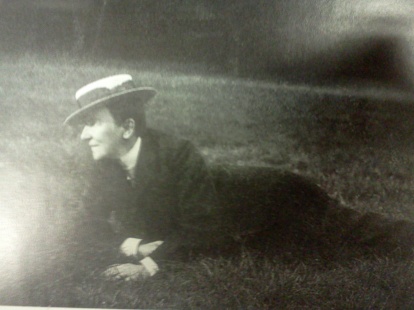

Image via Chadwick 2011.

Jane’s ability to tackle any situation she found herself in was one of her best traits. One of the most famous stories about her shows this clearly. While in Susa, during the transport of supplies and artifacts across a fairly wide river, Jane was forced to cross alone on the raft weighted down with cargo. She reached the other side without incident and apparently managed to unload the raft herself. However, while waiting for Marcel and the rest of her party to join her from the other bank, Jane was attacked by 8 nomads. Thinking quickly, and no doubt relaying on her military experience, Jane drew two pistols and held the group at bay, telling them “I have 14 bullets to use on you; go and fetch six more of your friends.” The nomads were a bit taken aback and reportedly held a standoff with her for 30 minutes as the rest of her party arrived (Gran-Aymerich 2006:49.)

The Return to Paris.

After the second season came to a close in Susa, the Dieulafoys and their team returned to Paris, where they were swept up in a whirlwind of activity. The found themselves busy setting up their finds in the Louvre, giving several interviews to the French media, Marcel began presenting papers on the Susa findings, and Jane received the Medal of Honor during the opening ceremony for the Acaemenid rooms, honoring her for her contributions in the war in 1870 and her efforts in Persia (Gran-Aymerich 2006:53, Zagria 2012.)

It was after this return to Paris that Jane permanently gave up women’s dress. She cut her hair short and wore only the best of Paris men’s fashion (Gran-Aymerich 2006:52 Adams 2010:56.) This is actually a stark contrast to the Jane of the past. When Jane had traveled in Persia in 1881-82, she admitted to being ashamed of her shaved head and dirty men’s clothing (Gran-Aymerich 2006:43.) Something changed during the Susa excavation to make her swear off female clothing for the rest of her life. She’d always expounded on the freedom men’s clothing afforded her, the simplicity of men’s dress, and the security being mistaken for a man gave her. Perhaps, the hassle of French Victorian women’s dress was just too much to squeeze back into after nearly ten years in men’s clothing, if so, can we really blame her?

Sadly, The Dieulafoys would never see Persia again, the political winds moved against them barring them from returning for further excavations (Gran-Aymerich 2006:56.) Still, this didn’t cure the archaeology bug. The Dieulafoys turned their attention to Spain and Portugal in 1888. Where they would work until 1914. These new investigations furthered Marcel’s original work on the oriental influence on medieval architecture in the west, only now he worked to connect the church and the mosque (Gran-Aymerich 2006:58, Adams 2010:60.) Jane again took her trusty camera with her everywhere, again creating a vast amount of images of an unknown land.

Morocco and the First World War.

When the first signs of World War I reared its head, Jane began urging more women to get involved in the army administration. She urged that women be allowed to take over the daily administration in order to free up men for the role of solder. This suggestion was popular among the populace and had a great deal of support. However, the government and the military alike didn’t agree, demanding that a woman’s place was in the home and dismissed Jane’s efforts (Gran-Aymerich 2006:58.)

When war was declared in 1914, Jane again accompanied her husband to Morocco despite a governmental decree say that women were to stay home (Gran-Aymerich 2006:59.) Jane claims that she never received the decree, but frankly, I doubt she would have agreed to stay at home and send Marcel off on his own. Despite this small hiccup in her early relations with Marcel’s Commanding Officer, the Dieulafoys were able to convince him of the benefits of excavating the Hassan Mosque, and they were given permission to do so.

Since Marcel was still needed by the army to build the hospitals buildings and other support buildings, Jane was left to be the leader of the excavations (Gran-Aymerich 2006:59, Adams 2010:60) Through her work and direction the Hassan Mosque was quickly recovered and restored (Gran-Aymerich 2006:60). This excavation and restoration worked to create goodwill with the local people in Morocco. It impressed Marcel’s commanding officer so much he requested they plan the excavations for a new site, the Roman city of Volubilis (Gran-Aymerich 2006:60.) Originally, the Dieulafoys were to carry out the excavations themselves, but sickness finally was able to slow down Jane.

During her time in Morocco, Jane devoted her days to the excavations and her evenings to working in the Hospitals with the wounded soldiers. The war raved the French troops and created unavoidably unsanitary conditions. From this Jane contracted amoebic dysentery while aiding the recovery of French soldiers (Coudart 1998:68). Sickness didn’t slow her down at first, she managed to finish the recovery of the Hassan Mosque and then consult on the recovery efforts of Volubilis (Gran-Aymerich 2006:60.) Still the sickness eventually overcame her, and she and Marcel returned to France in an effort to see her recovered (Gran-Aymerich 2006:61, Adams 2010:61.)

Had they simply stayed in France, she may have outlived the illness, but neither she nor Marcel could keep themselves from the war effort, and they returned a final time to the front only to have Jane fall ill again. For six month Jane tried to recover from the dysentery that had a firm hold on her now. In the spring of 1919, at the age of 65, Jane died in Marcel’s arms in their home in Paris (Gran-Aymerich 2006:61, Adams 2010:61.) Death proved to be the only thing that could separate them.

For his part, Marcel missed her dearly, and gave her credit for all their work together. He said half of his honors were hers, and without doubt, her contributions to Persian archaeology were as impactful as his (Iranica 1995.) Marcel would outlive her by only 8 months, succumbing to illness as well (Gran-Aymerich 2006:61, Adams 2010:61.)

There is so much to say about Jane Dieulafoy. Fortunately, most of Jane’s journals, notes, photographs, and personal correspondences survive, so we have a very clear picture of the woman that Jane was. She didn’t see herself as an individual, she saw herself as part of a team with Marcel. From all accounts they saw each other as equals in all things, and Jane took her marriage to him very seriously. Despite being a feminist of the time, she was very much against divorce and incorporated that theme into her novel Déchéance (Iranica 1995.) She always saw herself as female despite her masculine dress. She stayed a strong advocate for women, creating literary awards for her fellow female writers and supporting women’s efforts during the war. She was constantly active in life as well, even when she couldn’t be excavating or exploring, she was writing about what she had seen and encountered. She was fiercely patriotic, participating in two wars not just because of Marcel, but because of their common love for their country.

She is an excellent addition to our Mothers of the Field because of her discoveries in Persia, her work in Morocco, and her meticulous modern recovery efforts at both locations. Her photo-documentaries and writings of Persia and Spain added much needed volumes to research of those areas. She was a skilled and capable crew chief and site supervisor, and the results of her efforts are still on display today in the Louvre in France.

For more in this series check out Mother’s of the Field.

Resources:

Adams, Amanda

2010 Jane Dieulafoy: All Dressed up in a Men’s Suit. In Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists and Their Search for Adventure. Pp. 41-63. Vancover bc Canada: Greystone Books.

Arwill-Nordbladh, Elisabeth

2008 Twelve Timely Tales: On Biographies of Pioneering Women Archaeologists. Reviews in Anthropology. Vol. 37 Issue 2/3, p136-168. 33p.

Chadwick, Frank

2011 Historical Steampunkers — Jane Dieulafoy. <http://space1889.blogspot.com/2011/04/historical-steampunkers-jane-dieulafoy.html> Retrieved February 7, 2013.

Coudart, Anick

1998 Archaeology of French Women and French Women in Archaeology In Excavating Women: A History of Women in European Archaeology. Margarita Diaz-Andreu and Marie Louiese Stig Sorensen, eds. Pp 61-85. New York: Routledge.

Encylopaedia Iranica

1995 Dieulafoy, Jane Henriette Magre. Encylopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/dieulafoy-1. February 7, 2013.

Gran-Aymerich, Eve

2006 Jane Dieulafoy In Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists. Getzel M. Cohen and Martha Sharp Joukowsky, eds. Pp. 34-67. University of Michigan Press.

The New York Times

1916 Mme Jane Dieulafoy Dead.; Explorer and Author Fought Through Franco-Prussian War. The New York Times, May 28, 1916. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40B17FD3A5812738DDDA10A94DD405B868DF1D3. February 7, 2013.

Zagria

2012 Jane Dieulafoy (1851 – 1916) photographer, archaeologist, writer. A Gender Variance Who’s Who. http://zagria.blogspot.com/2012/05/jane-dieulafoy-1851-1916-photographer.html#ixzz2g6rH1ouP Retrieved February 7, 2013.

I found this biography fascinating. I looked on gutenberg.org and several of her books are available there; unfortunately none in English! I’ll see if I can’t find some at the library.

LikeLike

Hello there, we recently received a copy of a Jane Dieulafoy’s book which bears her signature along with a lengthy inscription. I was wondering if you would be able to help me determine its value, or point me in the right direction to someone who could? The book itself is in poor condition and merits repair. I would be happy to send some photos. Thanks for your time!

Please contact me at lastwordbooks@gmail.com if you have any information, or questions.

-Sky Cosby

Last Word Books & Press

Earthlight Books

LikeLike

I wouldn’t know where to start with that, I would assume you’d want a book historian of some sort? I mean, that sounds really cool, but its way outside of my expertise. Have you tried contacting a museum?

LikeLike

Thanks for your reply, I’m on the case. 🙂

LikeLike